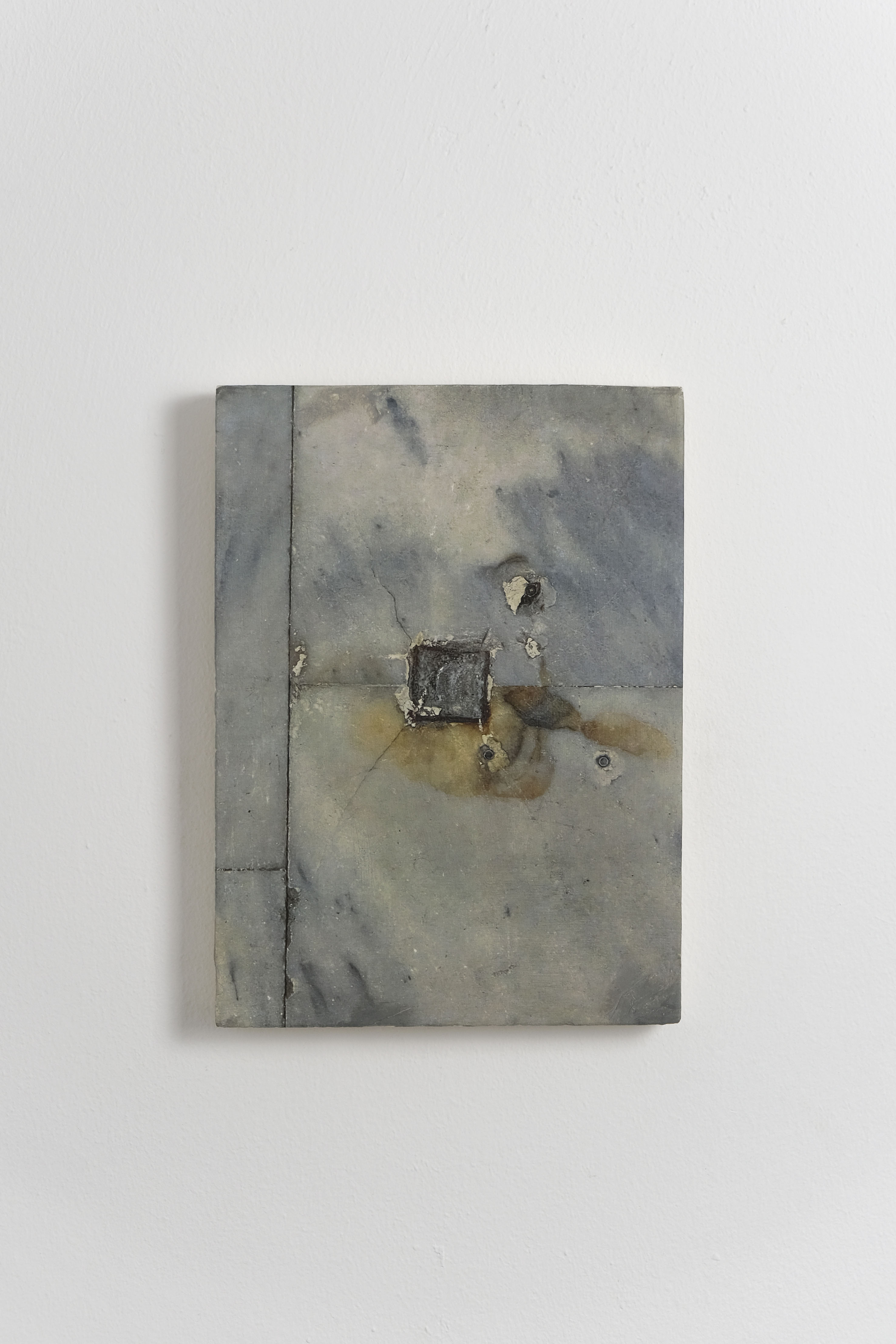

We Never Had Winners, 2021

archival pigment prints, archival pigment prints mounted on MDF board, archival pigment prints mounted on board, archival pigment prints framed in orange acrylic glass, mixed media on paster slabs, photographs transferred onto plaster slabs, digital print on vinyl, found vintage stereoview cards, plaster, brass tube, rope, glass, found concrete blocks, wood, metal

archival images: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1911 © & The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cesnola Collection ©

dimensions variable

archival pigment prints, archival pigment prints mounted on MDF board, archival pigment prints mounted on board, archival pigment prints framed in orange acrylic glass, mixed media on paster slabs, photographs transferred onto plaster slabs, digital print on vinyl, found vintage stereoview cards, plaster, brass tube, rope, glass, found concrete blocks, wood, metal

archival images: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1911 © & The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cesnola Collection ©

dimensions variable

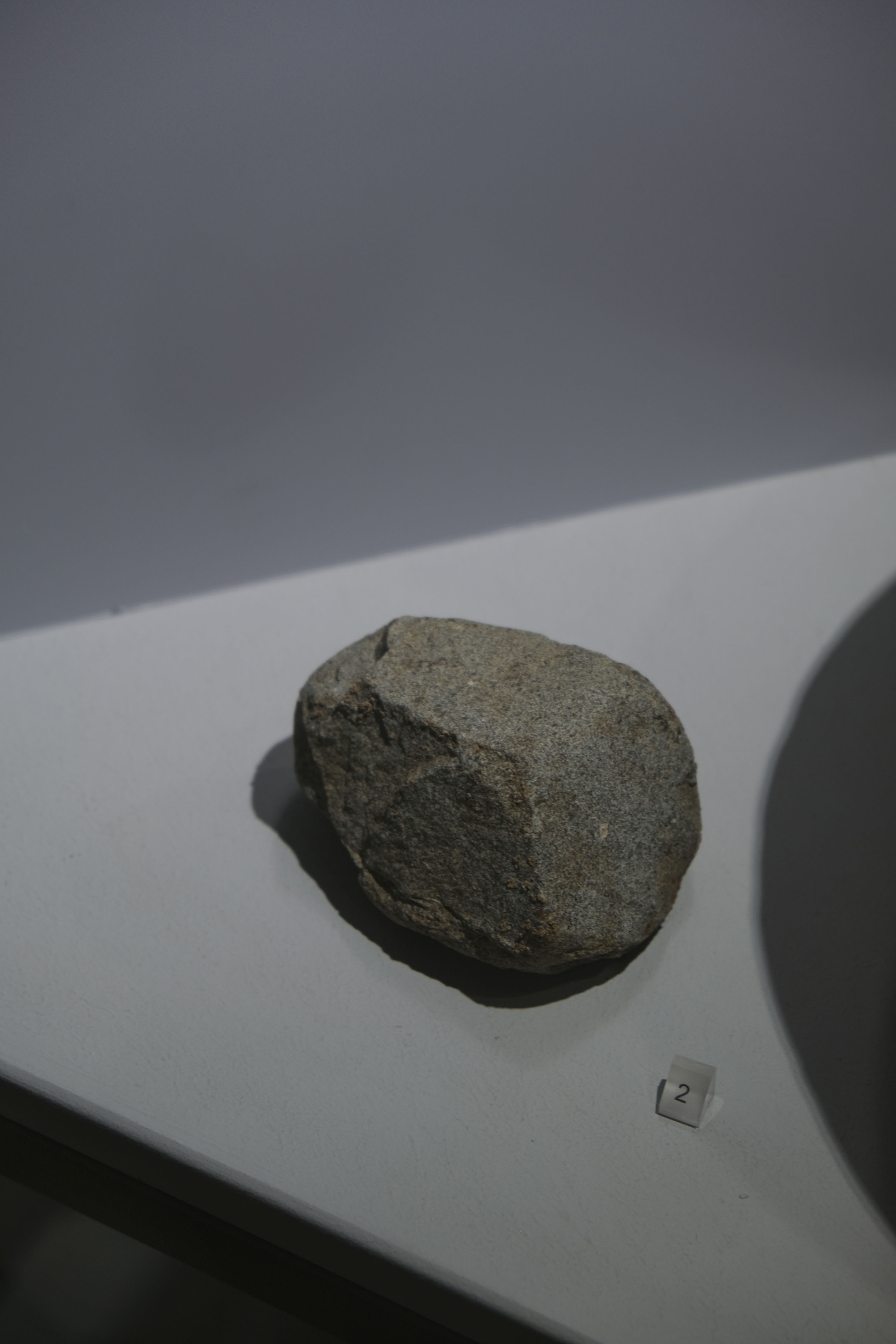

We Never Had Winners acts as a starting point of

reference to the three-part project titled Propaedeutics

on Memorial Structures Vol. I, II & III, investigating

the social, political and cultural condition of memorial monuments in Cyprus. This

last part considers the monument and its extended function as an object, its

symbolic use of material—an act of geological appropriation where the material

itself is an indicator of an-other historical time—as if bridging the past and the

future in present time. Material objects that become memory-agents, monuments, are

being transformed into emotional

historical artifacts through which contested history (or histories) can be

constantly (re)inscribed.

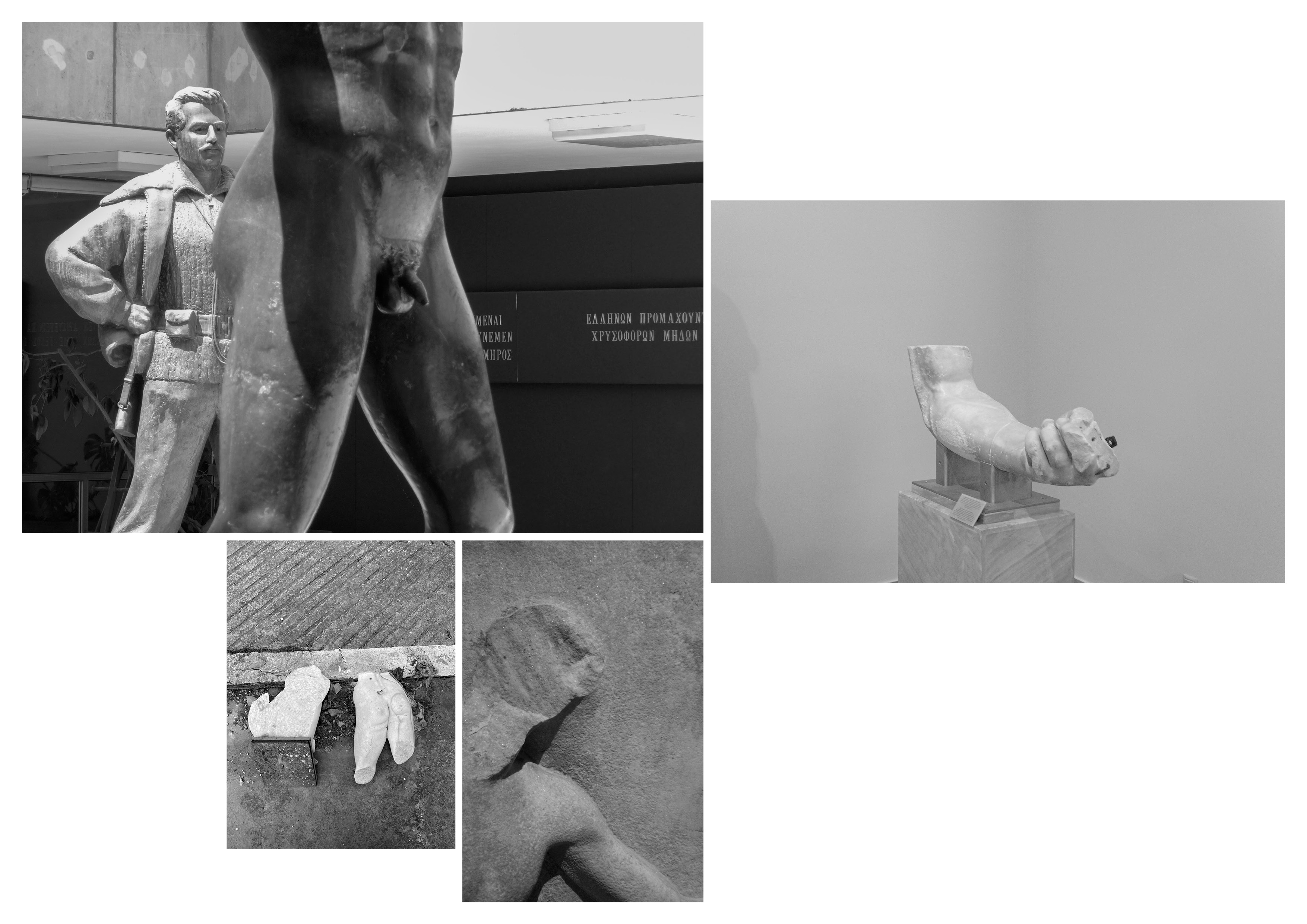

Questioning the complex historical and cultural assimilation of the Greek national narrative in Cyprus—an ideology that shaped the predominant understanding of a Greco-Cypriot, or more precisely of a Hellenic identity on the island: the movement within Greek-Cypriots for the campaign of Enosis, and later for the declaration of Cyprus as an independent state in 1960—the work poses a paradoxical statement on the nation’s “failed” symbols of victory. Despite a seemingly celebratory establishment of the Republic of Cyprus, the underlying religious, cultural and political conflict amongst various groups of both Greek- and Turkish-Cypriots urged the nationalist political elite towards a passionate and immediate declaration of all those who fought for the country as national heroes. Tracing their historical context as far back as the 1821 Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire, Greek-Cypriots fervently wanted to validate their own, and intensely participate in the lineage of Greek heroes. Elevating their dead war heroes onto celebrated pedestals as glorious symbols of national sacrifice and sanctity was an attempt by Cypriots to claim their virtuous right in political and national freedom, but most importantly to visibly claim and re-affirm their Greekness; one that stipulated cultural, national and religious identification with the motherland, Greece, and therefore permitted some form of participation in a glorious historical narrative.

Questioning the complex historical and cultural assimilation of the Greek national narrative in Cyprus—an ideology that shaped the predominant understanding of a Greco-Cypriot, or more precisely of a Hellenic identity on the island: the movement within Greek-Cypriots for the campaign of Enosis, and later for the declaration of Cyprus as an independent state in 1960—the work poses a paradoxical statement on the nation’s “failed” symbols of victory. Despite a seemingly celebratory establishment of the Republic of Cyprus, the underlying religious, cultural and political conflict amongst various groups of both Greek- and Turkish-Cypriots urged the nationalist political elite towards a passionate and immediate declaration of all those who fought for the country as national heroes. Tracing their historical context as far back as the 1821 Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire, Greek-Cypriots fervently wanted to validate their own, and intensely participate in the lineage of Greek heroes. Elevating their dead war heroes onto celebrated pedestals as glorious symbols of national sacrifice and sanctity was an attempt by Cypriots to claim their virtuous right in political and national freedom, but most importantly to visibly claim and re-affirm their Greekness; one that stipulated cultural, national and religious identification with the motherland, Greece, and therefore permitted some form of participation in a glorious historical narrative.

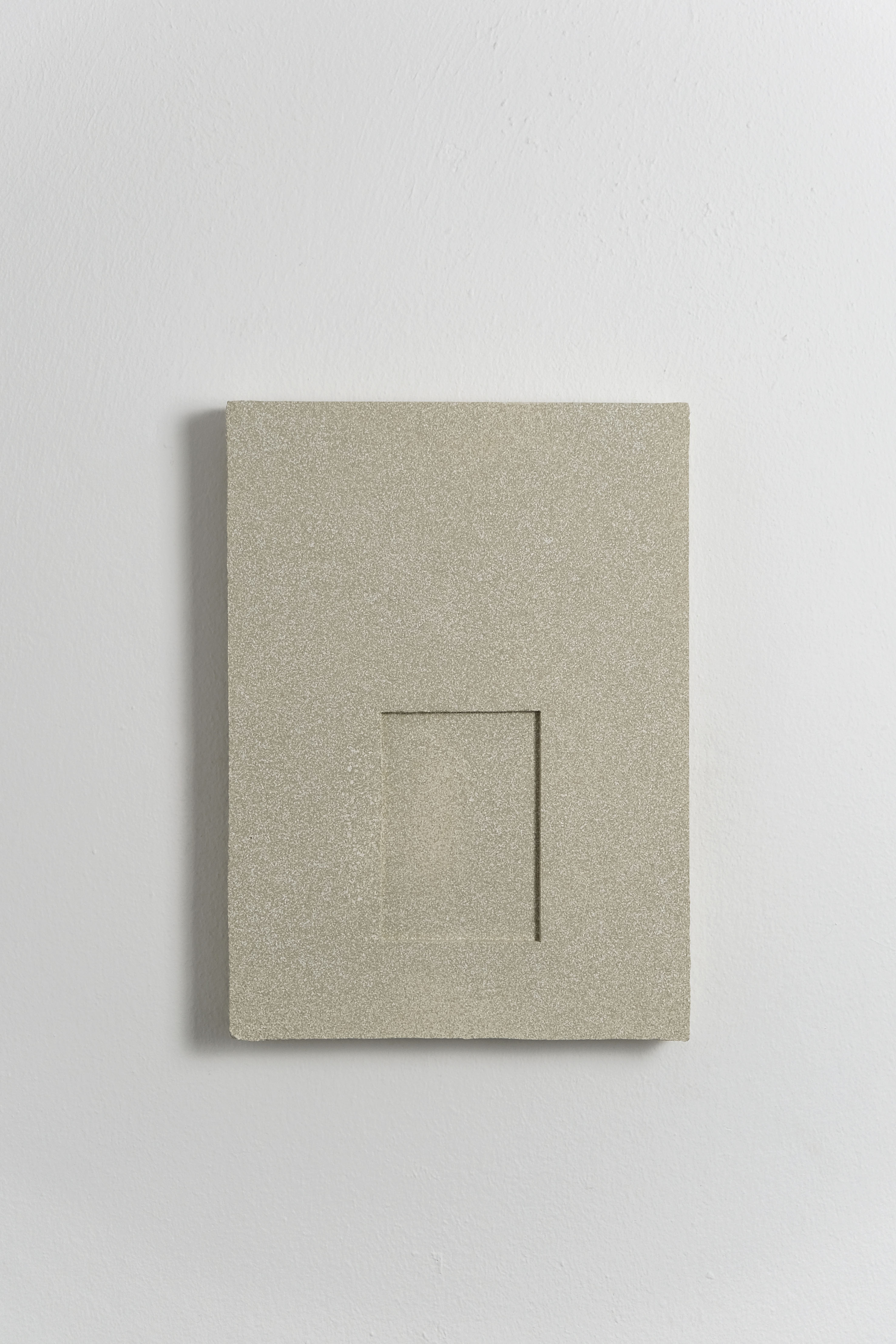

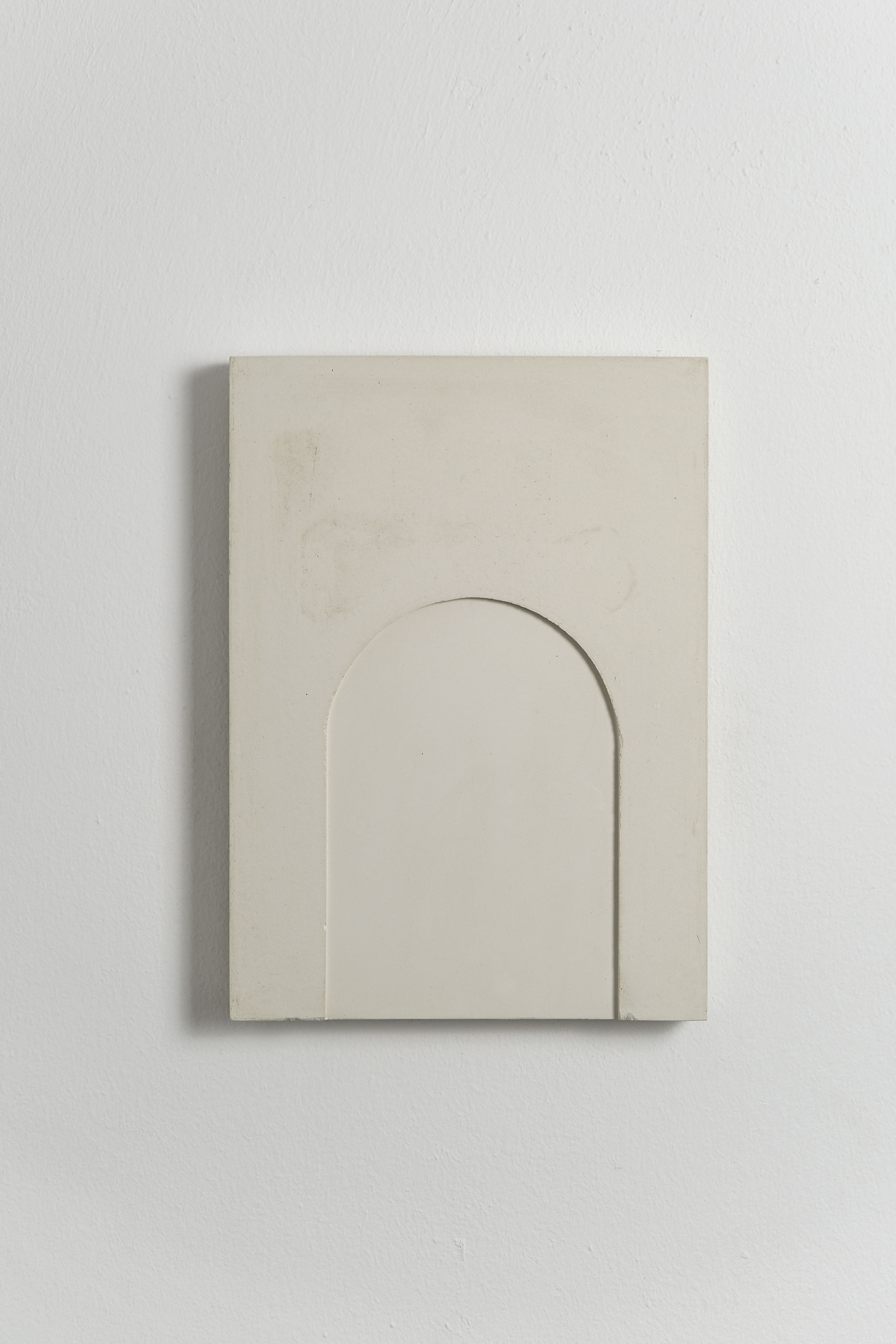

Employing the

photographic medium as an interpretive act of the material object, space and

time, the project dissects the associations between material and structure,

between structure and its visual representation, and between representation and

its simulated-signified historical narrative. The work adopts an artistic

research approach (both in its production and presentation) through which

photographs, photographic archives, found images, objects and material traces

form visual constellations of selected sequences and fragmented narratives,

allowing for multiple readings and associations. Images of Classical Greek

sculpture, fragments of marble, fabricated artifacts, as well as visual

displays of both Greek and Cypriot archaeological museums are combined and

juxtaposed, with visual accounts and traces of memorial monument surfaces. Photographs

and images that act as visual cues point to a research display of a museum

collection, a display that brings into question both the institutional function

of a museum as a cultural act, and its effect on articulating historical and

cultural narratives. The constructed archive—both subjective and re-structured

as artistic practice— brings into question the representation of

representations; the material object and its photographic image as means of

referral and reciprocal equivalences in displaying cultural residues.